All we can do is watch. She sleeps with her mouth open, a gaping void with three teeth, the two in front and one more after a gap. Her breathing is labored and noisy, currently about nine breaths per minute, but subject to change. One bulging eye is part open but blind, we think. Her skin, mostly purple now is so thin it barely covers the bones that protrude at the joints. Her legs, once her great pride now just pale sticks. My eyes trace the purple veins in her hands and watch the pulse still beating in her neck. She looks as if her still-working organs would be visible beneath the nightgown.

When she wakes she seems agitated, tries to speak but can no longer form words. She moans and stretches out her arms as if seeking a human touch and my embrace – hesitant from fear of hurting her or a lifetime of awkward affection – does seem to comfort her, or so I choose to think. We talk to her, not knowing if she can hear. We tell her we’re here, we love her and we’ll be all right when she leaves. Nothing that has gone before matters now. It’s OK for her to go now, we say, but she can’t agree. We give her permission but she has no more control of this than we do. Or does she? Is she fighting to stay alive, raging “against the dying of the light” Who can say?

It seems so unlikely, it was never a happy life, why fight to continue it? Because her lack of faith leads to fear of the unknown? Maybe.

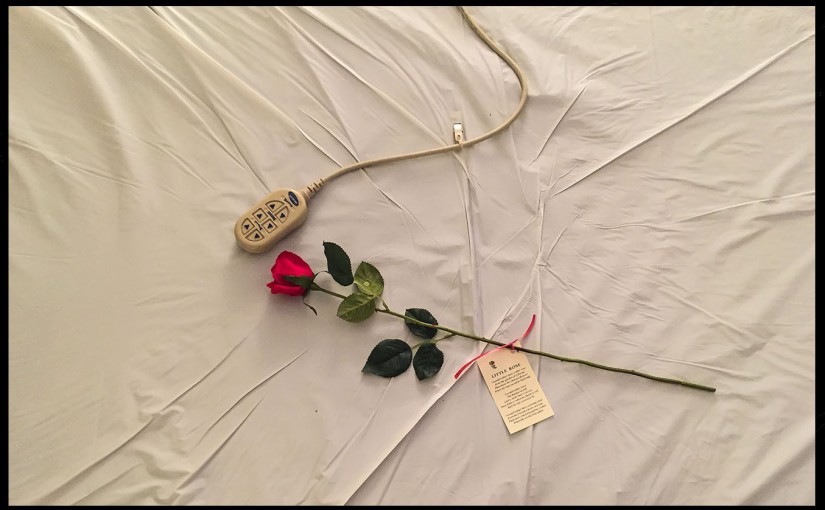

There is a nurse from hospice and a full time aide. They watch “Ellen” with the sound off. They chart every event, record imperceptible changes. They will not leave her alone and they won’t leave us alone with the morphine. They will keep her comfortable but they won’t speed her journey. They say if we have private thoughts to express they will leave the room for a moment. I can’t think of anything I need to say.

They tell us to talk to her, reassure her, tell her it’s OK but I don’t think she can hear, or could understand if she had somehow regained the hearing she lost years ago. I think this advice is meant for us, to let us feel we are doing what we can, to comfort us. They tell us there may be moments of clarity, or not.

Her breath is shallow now and has fallen to seven per minute. “American Idol” with sound, kept respectfully low. A swab with water for dry lips causes her to close her mouth tight. She wants no more. She sleeps. Does she dream? Sometimes there is eye movement beneath the lids but does it signify a dream?

And she wakes and begins to moan. It’s too high pitched and scratchy to be a moan but it’s not a whine. It sounds like an old 78 recording of a soprano past her prime. It is the sound of anguish, of reaching, of need. The nurse administers morphine, Atavan, and Seroquel by syringe without needle in her mouth, then massages her throat to make her swallow. She sleeps again.

So we watch – and look for signs of change. Has her breathing slowed? Or is it faster? Have her feet turned purple? Blood pressure down but sometimes it rises before death. Pulse? There is no pattern, our deaths, like our lives are unique. And this is the one body process we cannot know from the experience of others.

The Today Show. No change.

Meredith

Divorce Court

Weight Loss Program Advertising and Bankruptcy Lawyers

One Life to Live

Local News

No change.

We are seven waiting for mom to die.

Her hospice nurse and aide

The three children

The two grandchildren

Waiting

No change

Her breath is a little slower now, maybe six per minute and the time between is longer.

Watching her breathe, ten or fifteen seconds between breaths is a lifetime. It seems too long. I think she’s gone but no, her chest slowly rises and falls again accompanied by a raspy moan.

It will be 83 degrees and sunny tomorrow.

©2015 Ron Scherl