-Bonjour Joan, bienvenu à Paris.

-Merci beaucoup, Claude, I’m so happy we could meet here at the museum. Thank you for inviting me.

-You’re very welcome but before we look at pictures, I need to make a little confession. When I received your letter, I thought you were the girl who wrote songs, and I wondered what we would have to say to each other. Don’t get me wrong, they are lovely songs but not really my thing and I’m relieved to find you are not only a painter, but one whom I admire.

-Merci Claude and may I say, coming from you it is a great compliment.

-Shall we sit for a cup of tea? We cannot smoke in the galleries. Even I am forbidden. Seems grossly unjust, nevertheless…

Monet lit his pipe, Mitchell fished a cigarette from her purse, and they began to talk.

-I love your later work. I appreciate what came before but they do not move me in the same way. The haystacks, Rouen, London, they are beautiful to be sure, but to me, they are of the past. But the work from the last few years of your…

She stopped, suddenly unsure of what to say.

-A technicality, my dear, we will speak of it later, but I’m beginning to understand your reputation for speaking your mind. In any case, the later works are certainly more about impressions than observations. They are what I see but filtered by my senses and memories. Perhaps I should call them sensations?

-I’d stick with impressions, Claude, it feels right.

-Very well. I’m not surprised that the more abstract works most appeal to you.

-Yes, we speak the same language. But the power is also in your palette. It’s more expansive, mauves and reds are there. They never were before.

-That is true.

-And your brush strokes are freer. They flow as if you had learned to fly.

-I would like that. But, if I may, I see a similar progression in your art. I worried about your early paintings—all that black. I thought you were at war with yourself.

-Maybe so, or maybe it was a reflection of the world I lived in or the struggle for acceptance.

-Perhaps, but often I think that struggle is essential to art. If it’s too easy, one becomes a painter of toys, of poodles and balloons. But you grew. I thought you may have resolved some conflicts. Your work matured without softening, you drew us into your world and allowed us to feel the emotions within you. It’s a rare gift.

-It’s not something I can explain.

-There’s no need. It’s there for those who choose to see.

-And you, Claude. The world waits in long lines to share just a touch of your vision.

-Not really. Certainly, they attend my expositions, but only to take a photograph to prove they were there—here in Paris, or wherever—to people who really don’t give a shit. I’m not sure they ever see the paintings. But enough. I want to talk about color. After most of the black was gone, you began to add solid blocks of mauve and magenta at what seemed to me a most unexpected time and place.

-You don’t like them?

-On the contrary. They attract and refresh the eye, while adding gravitas to the entire composition.

-You did much the same.

-Close, but not the same. I splashed some similar colors among the greens and blues, but I have never painted those solid blocks with the same confidence as you.

-You’re very generous, but I’m not sure it was confidence I felt.

-All the same, I want to talk about your yellow. I don’t know how you do it. The color is astonishing, as if you are painting the sun. You seared my eyes and brought me joy at the same time. There’s nothing like it.

-I’d love to see your interpretation.

-They weren’t right. I destroyed them.

-I’m sorry.

-It’s quite all right. The world has you.

-I don’t know what to say.

-Nothing. But you should get together with Vincent. Now there’s a man who knows yellow.

-Those sunflowers. My God.

-Yes. They can make you believe.

-Almost. But tell me about what I see as your movement toward abstraction. No one else was there with you.

-The truth is I could no longer see very well. I think to truly understand, you must come to Giverny.

-I would like nothing more.

They looked at each other with a shared understanding, a true meeting of compatible souls.

-Claude, I have to ask. If it’s too painful you don’t have to answer, but—aren’t you dead?

Monet relit his pipe as he considered how to answer.

-Technically, I suppose that’s true, but the real truth is that my life is my work. And it remains, as will yours.

©2023 Ron Scherl

Don’t worry. I’m not going to get all snobby about this, wonder why people do it, and then blame Facebook. Not me. I live in the real world and I’d rather blame Facebook for much bigger crimes.

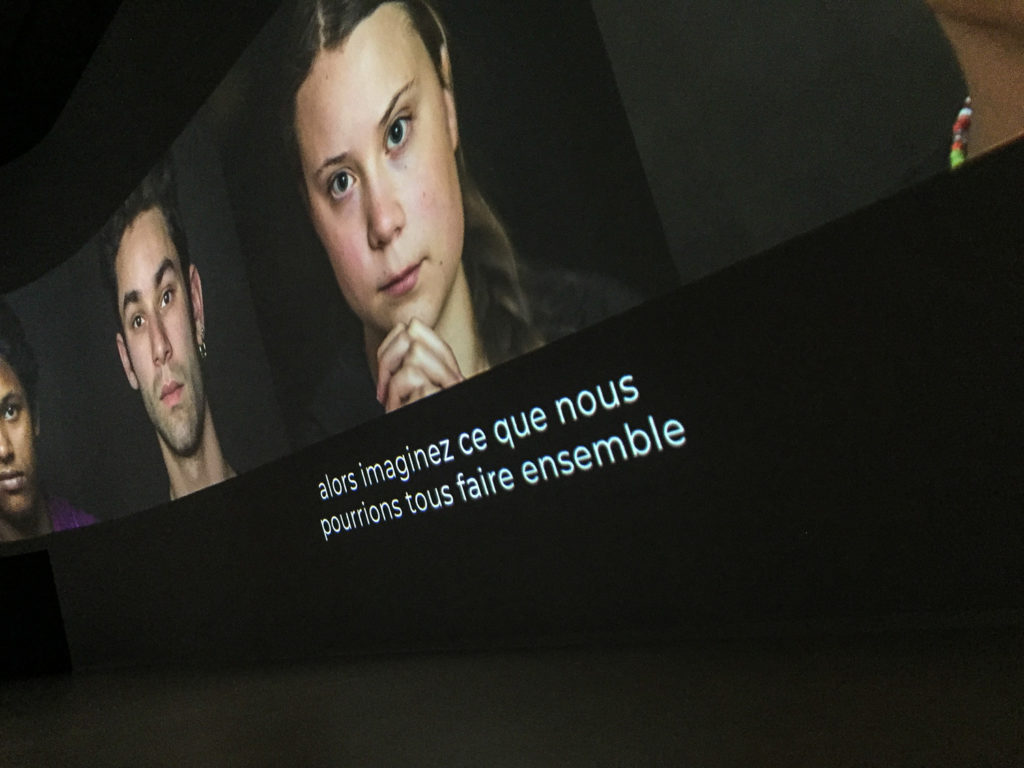

Don’t worry. I’m not going to get all snobby about this, wonder why people do it, and then blame Facebook. Not me. I live in the real world and I’d rather blame Facebook for much bigger crimes. I see nothing wrong with people taking pictures of art. I’m glad they do it. Glad they support the museums with their tickets and glad the museums have wised up and allow it. I’m not sure what people take from the experience, but it certainly can’t hurt.

I see nothing wrong with people taking pictures of art. I’m glad they do it. Glad they support the museums with their tickets and glad the museums have wised up and allow it. I’m not sure what people take from the experience, but it certainly can’t hurt. Shoot Pictures. Not People.

Shoot Pictures. Not People.

©2018 Ron Scherl

©2018 Ron Scherl